Screen Time and Your Child

Imagine a child alone in a home with bowls of fresh fruit and vegetables on the table which are mysteriously replenished each morning. At first the child is quite satisfied with their meals, and knowing a bit about nutrition and fitness from health class, they even feel a measure of satisfaction from their lifestyle. One day while exploring the space, however, the child opens a door into a room filled with boxes of candy.

Eating five Snickers bars is inadvisable and will probably make you feel a bit ill. Perhaps child regrets their ill-advised spree and go back to the fruits and vegetables the next time they are hungry. The child eats a lime and discovers that it isn’t as pleasantly sour as that apple flavored lollipop. What was once the subtle flavor of the banana doesn’t seem to taste like anything at all. Nor does the apple taste sweet. The effort of opening up a pomegranate or pineapple which once piqued their curiosity and whetted their appetite now seems numbingly inconvenient.

One of my favorite pleasures as an educator is to impart an idea to children of what it was like to live in different times or places. In a recent discussion in the Upper Elementary room, some students were shocked to learn that sugar was not a common foodstuff until the 19th century. “So their food wasn’t ever sweet?” a student asked. I explained that they thought their food was sweet when they had honey or fruit. They simply didn’t know what they were missing.

Many times while studying history with elementary students a student will bring up previous generations’ lack of television or video games. It is an understandable reaction; screen time has become as integral part of their live just as cane sugar has, and with similarly complicated consequences.

As the rate of technological and social change quickens, the truth is that gadgets and their use are changing faster than scientists and sociologists can study their effect.

It is clear, however, that screen time has measurable effect on the social, physical, academic, and emotional lives of children. In the new guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the hard limits are as follows: No screen time for children under two. For children 2 to 5, less than one hour. It gets more complicated for older children. “Children today are growing up in an era of highly personalized media use experiences,” they write, “so parents must develop personalized media use plans for their children.”

As adults, our thoughts and reactions are to a degree determined by the neural pathways we’ve reinforced by repeated use. It is for this reason why frequent complaining leads to a more negative mindset. It is why our negative reactions to stress are so difficult to root out. Conversely, it is for this reason why practitioners of silent contemplation, meditation, and prayer report a great inner calm.

Now, imagine the mind of a child, incredibly plastic and still under construction. The pathways they use now are already developing into what will become the most well-worn and easily travelled paths in their mind. If the child’s entertainment diet is passive and of low quality, that may contribute to certain problematic attitudes in the classroom. Foremost is the idea that fun is effortless and gratifies instantly. Difficult tasks are not seen as opportunities for growth but as unpleasant obstacles to be avoided.

The Mayo Clinic notes that, “it's crucial to monitor the shows your child is watching and the games or apps he or she is playing to make sure they are appropriate. Avoid fast-paced programming, which young children have a hard time understanding, apps with a lot of distracting content, and violent media. Eliminate advertising on apps, since young children have trouble telling the difference between ads and factual information.”

Just as we humans love fatty, salty food due to our primordial craving for those two rare nutritional needs, we love distraction, gossip, and vicarious violence. Our interest in novelty and the lives of others were once the advantages of our long ago ancestors that allowed them to excel as humanity raced out of the horn of Africa to explore the world. Those same qualities, deep and dormant in our brains, are what keeps us and our children glued to screens until we turn off the blue light late in the evening and wonder why we can’t sleep.

This is no accident. The companies that make apps and video games are using this knowledge of neuroscience to design addictive programming. For children, that means making things faster, brighter, and louder. It means replacing humor based on language and context with non-sequiturs and silly voices. It replaces the metaphorical and the analogical with the literal. In short it replaces engagement with frontal brain function with tickling our basest instincts.

It is this kind of programming a child was thinking about when they told me recently that they didn’t like movies because they were too long. If a movie is too long, what will they think of a novel?

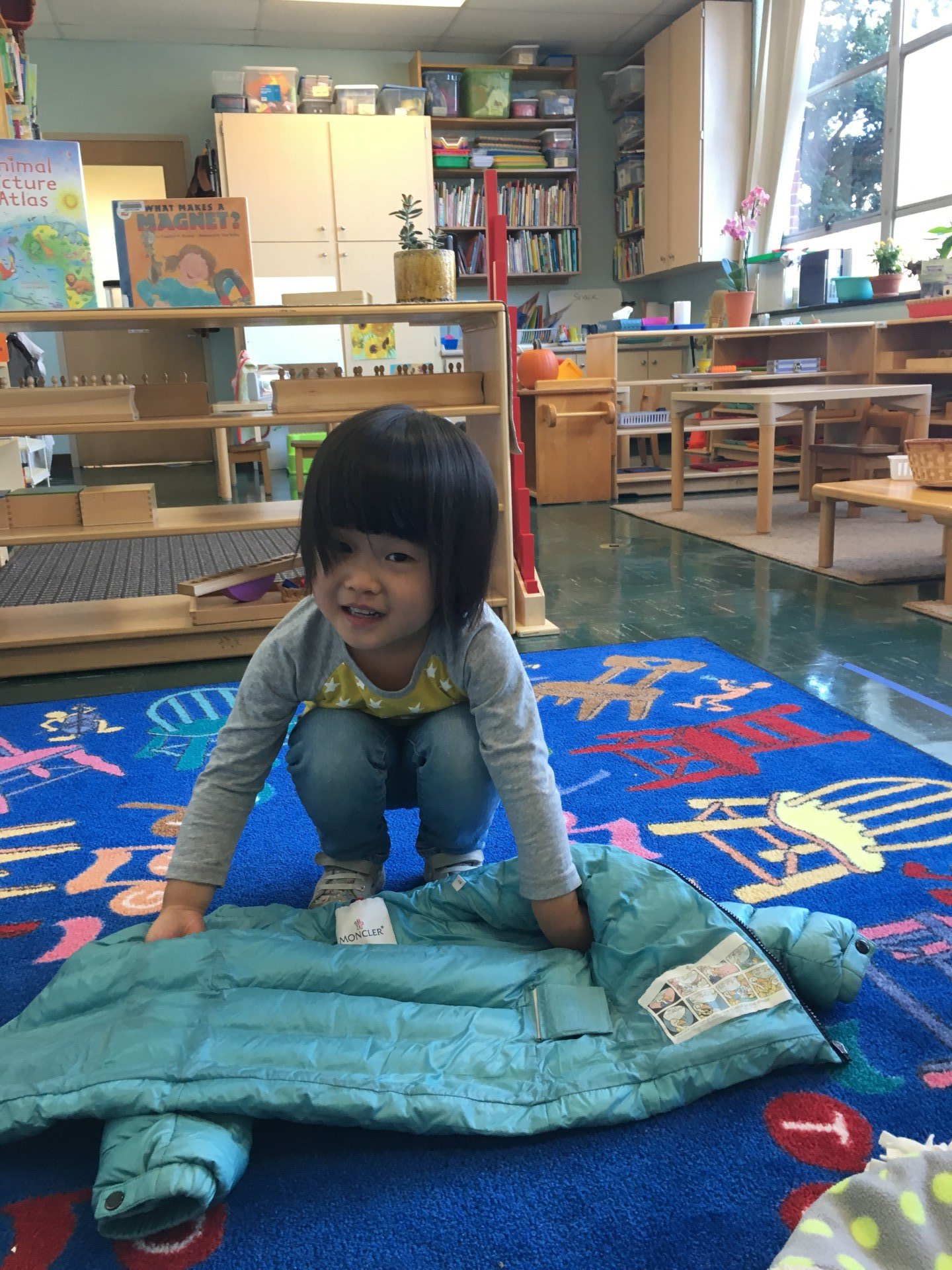

From a teacher’s perspective, the three things that screen time largely replaces is reading, sports, or unstructured play. The importance of the first two is beyond question, but first a word on unstructured play: it is the fancy scholarly term for what happens when you are consumed with some task and you look out the window to see your child playing with the cat, the neighbor, two rocks, and a stick. Whether or not there is supervision it is child-driven, child-planned, and child-centered. There are no rules, or if they are rules they are made up on the fly as two or more children learn about collaboration, communication, and compromise in real time. It is a child’s social education. For a child of 2-5 years old, it is at least as important as reading.

For the older children at our school, the most important task is that they develop a love of reading and the practice of it. Reading builds the knowledge of vocabulary and spelling which frees up time for that student to focus on other interests during the school day. It improves memory and analytical thinking skills. It assists the child’s development of focus and concentration. In the Montessori classroom this is called “normalization”. The normalized student is not bored or overwhelmed but can assert their own will to learn on their own terms. In the home this could simply be a child who is comfortable with silence.

How does one reduce and control screen time in their own home? There are as many answers to that question as there are students at the school. What is essential, though, is for the child’s parents to agree on a plan for their child’s diet of screen time and to cooperate in firmly enforcing the limits which are set. The child may be bored at first, and that is okay. The cultivation of the ability to endure boredom is linked to the practices of patience and tolerance. They may devour a book or go turn over rocks looking for bugs. They may count the bumps on the popcorn ceiling. It is okay. It is in that quiet that our truest natures reveal themselves. It is where we can hear the still, small voice of our conscience. Not everything good is easy. Not everything good is loud.